There is the lack of hygiene, resulting in many diseases, unemployment and the resulting precariousness of life, the very acute problems linked to education, to say nothing of AIDS and the increasing overall insecurity. And people have very limited resources to face up to all that. The famed solidarity of the large African family is in tatters. Especially in the towns, traditional society has broken down, the social fabric is completely in shreds, and the old-style ‘poor people’s welfare state’ no longer exists.

Just being there

People often ask us, “So what are you doing here?” The answer is provided by the customary form of greeting in Wolof, the most commonly used language in Dakar. When you greet someone, you ask, “What are you doing?” The reply is simple, “I am here,” or sometimes, “I’m here, that’s all.” So when people ask what we are doing in this neighbourhood, we can reply, “We’re here!”

And it’s no little thing to be here, really present to this neighbourhood’s life, praying, working, constantly welcoming people in the house and yet, at the same time, to remain even after so many years strangers often bewildered by a mindset we have only very partially understood. Not that that prevents a lot of joyful sharing. And it is no little matter to keep going, persevering amidst all the agitation: the noise, the loud-speakers, the smells, the mosquitoes, the heat, the dust, the water cuts or power cuts, the uncertain means of transport, etc….

Here we are, then, doing what we know how to do - praying, working to earn our living, welcoming, sharing. And all the time challenges turn up that we try to deal with according to the means, the charisma we each have: with no illusions about our capacity to change life for all these crowds of people.

Education

A lot of things are possible with the children. They’re always the first to welcome you, to react enthusiastically to any suggestion. Those attending the public schools in the neighbourhood suffer from severe deficiencies - overcrowded classrooms, the morning and evening crushes, systematic rote-learning (learning by heart and reciting aloud the day’s lesson, in Koranic style). The poor teachers are overstretched, forced to use the rod to maintain any kind of discipline. Every student moves up at the end of the year, to make room for the next batch. As a result, at the end of primary education a lot of them emerge virtually illiterate into an employment situation that is becoming increasingly demanding.

In leisure hours, then, in our house we propose activities designed to encourage awareness, creativity, and observation. The children have never held a coloured crayon or a pair of scissors, they have never looked at a flower or watched a butterfly emerge from its chrysalis. They have practically never been outside the neighbourhood; some have never seen the sea, though Dakar is built on a peninsula! So much to discover, dimensions to observe, attitudes to be learned in a world full of stress where reactions are often explosive.

There is a lot to be done as well among the young people, already inclined to give up before a future that seems to be completely closed. Encouraging them, inviting them to look after the children and so discover that they can do something, sustaining them in their studies, offering them books to read, a quiet place to study when at home they often have no silence and no light.

A few have been able to start working in our house, making puzzles or other kinds of toys. Such objects are sold, usually abroad, and the income allows them to pay for their studies and solve various family problems.

The same possibility is offered to a certain number of young women and mothers from the neighbourhood. They started by learning patch-work, a strict school for precision, and with that some create quilts, dolls, cloth animals, etc. With all of them, there is a daily struggle to maintain perseverance, regularity, as well as standards and quality.

Helping

All round us are family problems; babies badly cared for by ignorant mothers incapable even of making sure they receive regular treatment, people whom life has left wounded, complete lack of money toward the end of the month … to say nothing of so many different kinds of swindlers. We cannot do everything, we have to choose.

Especially because we also want to be present beyond the limits of our neighborhood. We are involved in projects among refugees, prisoners, people who are seropositive. We are encouraging the creation of informal, popular schools in the outlying areas as a way of making up for the weakness in the public education system. Then there is our involvement in the local Church, prayers organized in various parishes, visits to other parts of the country and in other countries nearby. There are no limits.

But how can we help? That is always the big question. How can we support, enable this person or that to get up and stand on their own, giving just the little nudge necessary and nothing more. If we “assist” we paralyse them, people will become our clients, our parasites. There are those who look for nothing better. We would need enormous sensitivity and discernment to do just what is needed, neither too little nor too much, every time. Maybe we succeed sometimes. Above all when we try to work things out together.

Islam

Like every part of Senegal, our neighbours are mostly Moslem, although the Christian minority is quite vigorous. In the present, troubled times, it may not be so obvious to live in a neighbourhood that is 90% Moslem. Yet is can be so beautiful. Of course, to start with there was a time of observation. “Who are these ‘toubabs’ (Europeans) who’ve come to live among us? What are they after when they look after our children? Aren’t they going to try to convert them? As others have done.”

It took some time to gain the trust of the parents, and especially of those old “pillars of the mosque” who control the neighbourhood. Words are no use; in a milieu like this, they mean nothing much. Only truly disinterested actions, persevering in an attitude of respect for the religion of the other, allowed one day trust to be given so that those most reserved permitted their children to come into our house. Before they too crossed the threshold.

What does it imply to live today in the midst of a Moslem population? First of all, to regard these believers in a way that recognizes the work of God in them, that acknowledges the value of their faith, admires the authenticity of their prayer. And then to show a face of the Church that is not arrogant, a face in which perhaps can be glimpsed something of the life of Christ, in those in whom he lives.

We have not yet come to a stage of inter-religious dialogue. Our neighbours are simple people, often with little education, but with faith. There are beautiful friendships that arise with some, in which, sometimes, there are evocations of our common belonging among the descendants of Abraham. Together we are learning mutual trust, disarming stubborn prejudices on both sides, preparing the day when things might go further.

We should also help the local Christians, who on the whole get on quite well with their Moslem relatives, to get beyond certain fears, certain misunderstandings that are mostly common to both sides. Senegal, where there is a quite unique state of peaceful relations between the two religions, could go much further.

The children

Our greatest source of happiness in this adventure of fraternal living in Dakar is the children. Their faithfulness, affection, enthusiasm; surely they believe that we are helping them and that may be a little bit true. But if they only knew how much they help us to live, they would be very surprised.

Africa today is full of problems, overshadowed by threatening clouds, and often the thought of the future arouses a real sense of panic. But living in the midst of this whirlwind of children full of energy and resilience, who are back on their feet the moment they fall, makes it impossible for us to be really discouraged. They rekindle our hope.

Prayer

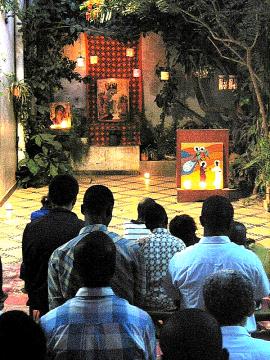

Each evening, local Christians, children especially, but also young people and some women, come to pray with us. Sometimes in the evening our chapel is too small, so we arrange the house’s inner courtyard, with the children unrolling mats, bringing out the little stools, books, candles, icons. We create a beautiful chapel there, with the sky studded with stars as its ceiling … crisscrossed by great bats and loud with the hum of mosquitoes.

Some of the children never miss a single day and sing heartily. As the years have passed, the songs from Taizé translated into Wolof have changed slightly to the rhythm of the tam-tams; their repetitive style blends perfectly into the local culture. During the times of silence, all the neighbourhood’s life, with the shouts, the noise, the calls to prayer from the mosques, come to inhabit our prayer.

TAIZÉ

TAIZÉ